Msasani and Masaki exist side by side, along old colonial boundaries for European settlement in Dar es Salaam.

The old colonial border in Oyster Bay, Dar es Salaam - Msasani and Masaki.

The beachfront in Nungwi, on the northern tip of Zanzibar island, is colonized with expensive multinational hotel chains which cater to the super-rich and can cost upwards of $7,000 per night. The strain that this puts on the service delivery system in this region (for electricity and water) is massive. Researchers found that, on average, tourists were using 16 times more fresh water a day per head than locals: 93.2 litres of water per day, whereas in the five-star hotels the average daily consumption per room was 3,195 litres.

This hotel in Nungwi, Zanzibar offers residences that can cost thousands of dollars per night.

Nungwi, Zanzibar.

Dar's city centre is a stunning mixture of the old and new, order and chaos. Above, the new Bus Rapid Transit line, similar to the one in Bogotá, cuts through the colonial centre of town with a graceful arc. The tall buildings, themselves a hodgepodge of styles and order, encircle one of the many dense slums in the Kariakoo neighborhood.

The Msimbazi river flows through the middle of Dar, and unsurprisingly informal settlements have sprouted up within the flood plain of the river. This relentless encroachment into the polluted river occasionally has dire consequences. The river ecosystem is beginning to take back these structures in the Jangwani floodplain from the owners who were forced out by flooding in 2017.

Abandoned homes in the Jangwani floodplain, Dar es Salaam.

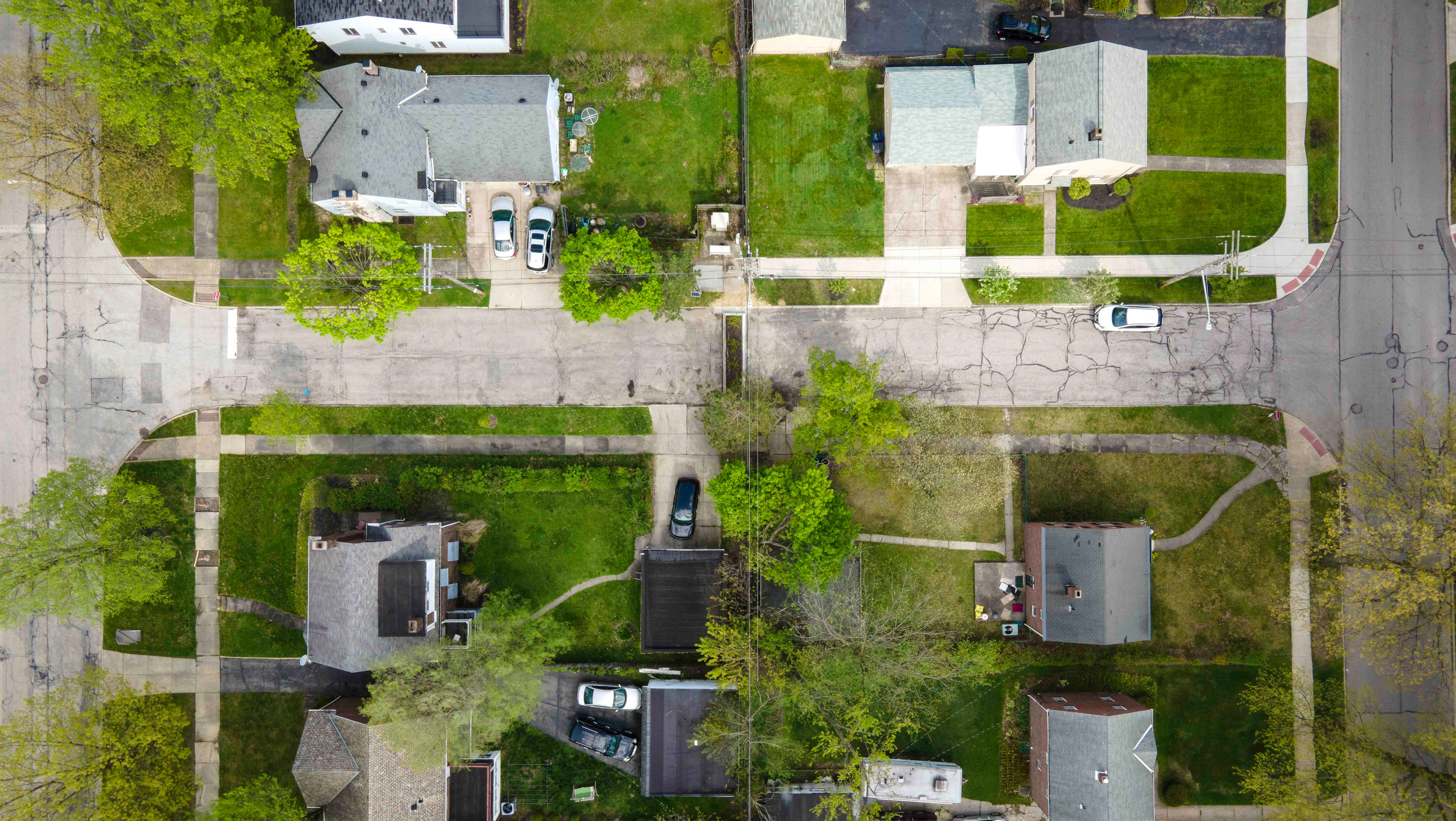

Mikocheni, Dar es Salaam.

Mikocheni, Dar es Salaam.

Another view of Msasani and Masaki, Dar es Salaam.