Luxury hotels inside a huge gated community in Nusa Dua, which controls access to the beach and the surrounding amenities.

White herons flying over rice fields near Seminyek.

Villas, hotels, and businesses have steadily replaced rice fields in the quest to service the island's massive reliance on tourism. In 2019, over 6 million foreign tourists visited the island.

Half-finished developments dot the island, this one in Uluwatu.

Luxury hotels near Ubud are carefully designed to harmonize with the surrounding rice fields and landscape, but major problems of water usage and economic benefits from such projects remain.

Development and speculation abounds in hidden copses of trees, ravines and farmland far from the dense bustle of the road network and prying eyes in Bali.

Bali's uneven water usage mirrors other resort destinations, such as Zanzibar.

Personal swimming pools at a resort in Uluwatu.

Stunning access-controlled luxury beachfront hotels dot the coast, including the Apurva Kempinski, where the G20 meetings were held in 2022.

Rice terraces are the defining characteristic of the Balinese landscape, carefully managed over hundreds of years in a system of water rights and coexistence. This system is steadily being disrupted as more and more development occurs on the island.

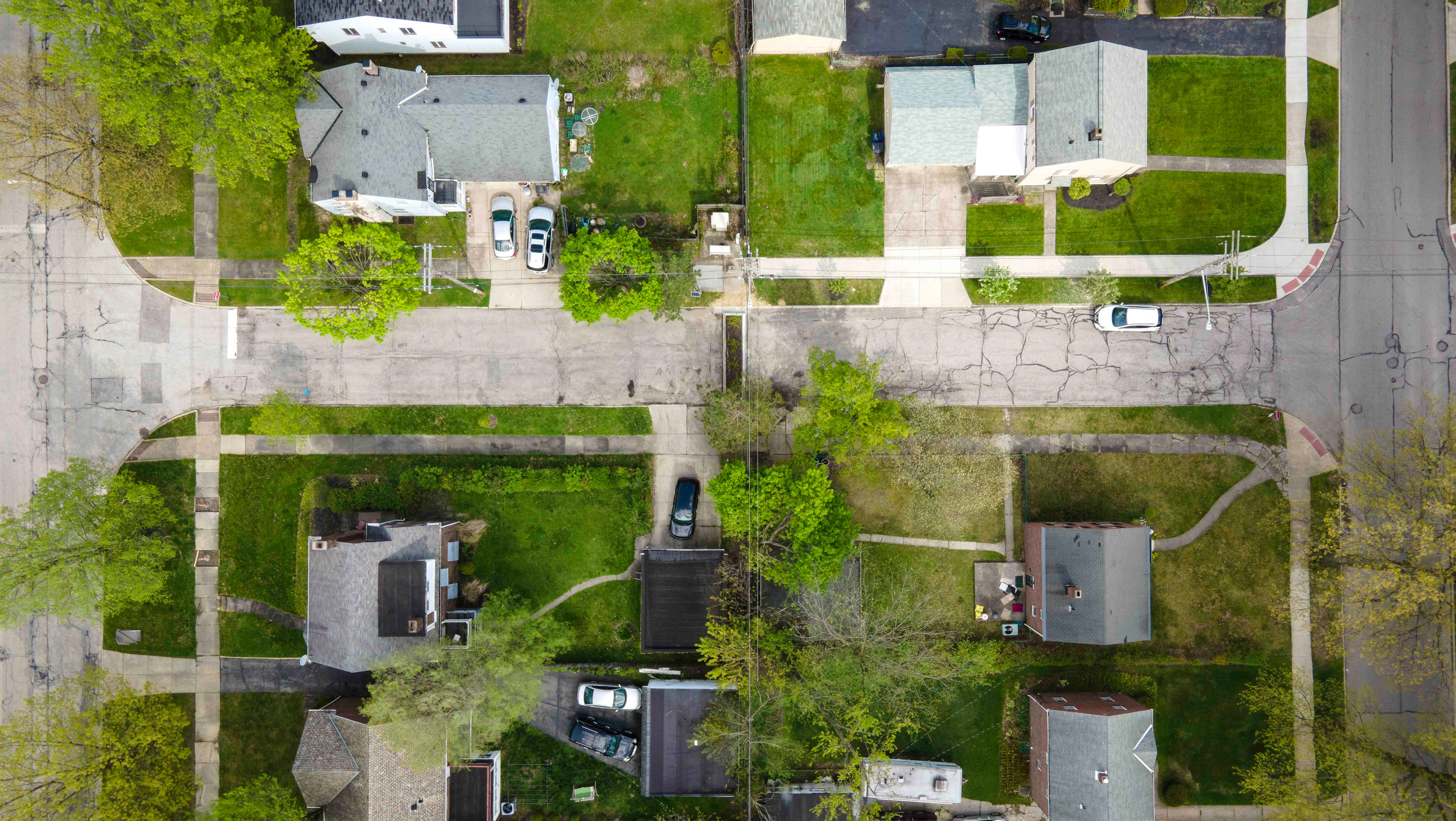

Development in the fields near Seminyek.

Unfinished development in Uluwatu.

"Parq Ubud", a development marketing itself as the "city of the future" takes shape near Ubud. The development's website bills itself as a "futuristic idea of a place where people with common values and interests come together."

Villas being built amongst the rice fields, Canggu.

Ubud, sunset.