Lake Michelle / Masiphumelele.

Contrasting zinc shacks with winter's green slopes on Table Mountain National Park.

Nestled between two of these affluent housing estates is the suburb of Imizamo Yethu. Imizamo Yethu (IY) is comprised of both a designated housing area and an “informal settlement” area, which is largely comprised of small shack dwellings which stretch up the steep slopes of the mountain behind it.

The shacks in this informal settlement reach right to the very edge of the demarcated area, in a densely packed jumble of tin roofs. In fact, even though the total area of IY is much smaller than the whole Hout Bay valley, the two have roughly the same population, 15538 vs. 17329. (City of Cape Town Census 2011)

The striking visual dissimilarities between the richer estate to the north, Tierboskloof, and IY are immediately apparent when viewed from the air. The line of trees which divides the two hides (several) heavily fortified fences, and many distrustful neighbors. In some cases, the houses (some with swimming pools) are just a stone’s throw from the shacks.

The most striking thing to me is the number of trees in Tierboskloof, versus the almost treeless IY. On the day I flew overhead, it was scorchingly hot, almost reaching 30 degrees. I imagined that the temperatures underneath the tin roofs must have been stifling.

Endless shacks stretch towards the summit of Skorsteenberg, the mountain which looms over IY.

Hout Bay / Imizamo Yethu.

The beautiful valley of Hout Bay means "Wood Bay", for the ample wood used to supply vessels on their journey round the Cape of Good Hope.

Penzance Estate borders IY to the south.

Vast differences side by side on the northern side of IY.

Little Lion's Head, as a strong westerly wind blows in off the cold Atlantic Ocean.

Shacks proliferate in Khayelitsha, Cape Town's biggest township. Over a million people live here. When I first visited in 2016, the shacks were not built past the dirt road in the center of the photo. Now, they extend almost all the way to the ocean.

Sweet Home was primarily a dumping ground for builder’s rubble like bricks, which you can still see being recycled on the side of the road today near the south end of the settlement. Services and conditions are poor. Vukuzenzele, just to the north, was developed in collaboration with a fund to provide affordable housing to South Africans. The visual difference between the two is stark.

Squalid conditions for thousands who live in the shacks of Nomzamo, with an interesting walled "Access Road" along the creek between gated estates.

Baden_Powell drive extends in a precarious strip of asphalt between the Cape Flats and the Indian Ocean, a windy, stark place were many Black and Coloured indivduals were forcibly moved to during apartheid.

Monwabisi Park, an informal area in Khayelitsha with tens of thousands of residents. Table Mountain is in the background.

Informal shacks alongside the large city dump near Muizenberg, south of the city.

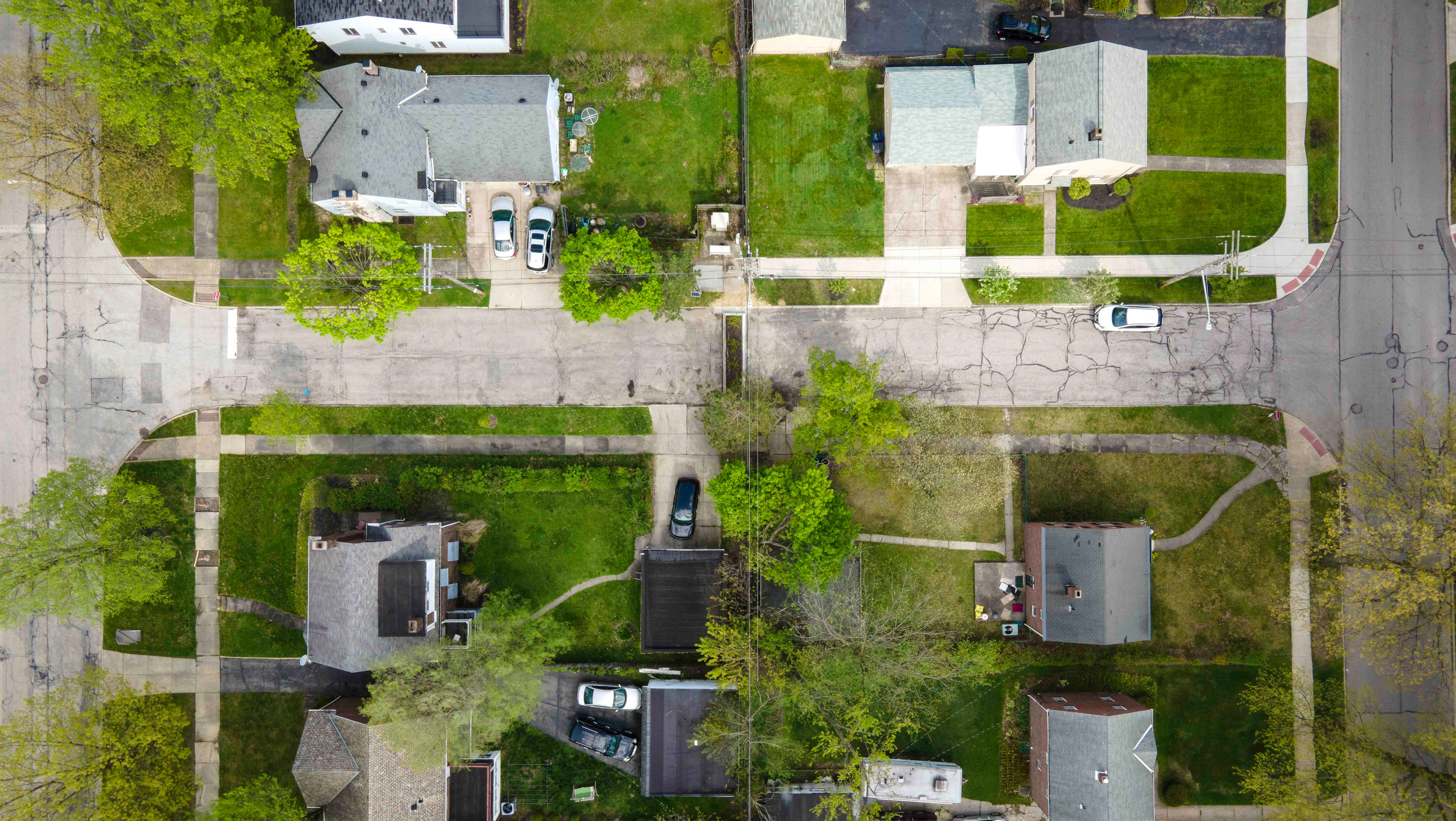

The organic network of roads and dwellings to the south contrasts sharply with the orderly, geometric patterns of the planned community to the north. This means much more than simply representing a difference in wealth, writes Diana Mitlin.

“Just as the community capacity building element provides an essential legacy in being a social asset that will help enable the community to address its future goals, so the development of physical assets provides essential assistance. In this case, the physical assets incorporate secure tenure, access to adequate services and improved living conditions. This enables families to have access to healthy living conditions and offers them the opportunity to accumulate resources. However, the development of physical assets is also important for another reason; it provides the arena within which collective skills and capacities can develop.”

Philippi.

Strand/Nomzamo.

A checkerboard pattern of inequality near Somerset West, with the former "black spot" of Nomzamo and several informal areas visible, about 40km east of Cape Town.

Shacks near Muizenberg, with the rich winelands of Constantia and Tokai in the background.

Farms and shacks near Dunoon, Cape Town.

The quickly growing neighborhood of Dunoon is at the end of the city urban structure, alongside the N7 highway to Namibia.

Shacks and the MyCiti bus yard along the N7 north of Cape Town.

Many people, including residents of the City of Cape Town's relocation site called Wolwerivier languish in poorly serviced settlements, far from jobs or other economic activity in the dusty periphery. This means that while they are not "side by side" in unequal scenes, they represent the hidden, and arguably more pernicious majority of impoverished South Africans, for whom the verdant peaks of Table Mountain represent an ethereal Shangri-La, glittering mirage-like on the horizon.

Dunoon.

Dunoon inundated by the Diep River just after a winter storm.

The Cape Floristic Region is one of only six on earth, and by far the smallest. It comprises the Cape Peninsula and a small part of the surrounding landscape. This otherwise arid part of Africa receives just the right amount of rainfall every winter to boast incredibly diverse and productive agricultural areas, which provide a striking juxtaposition to the hundreds of thousands who live in shacks on the periphery of the city.

2016

2017

2018

2019

2022

2023

2024

In a stunning display of contrast, Kayamandi sits at the top of a hill overlooking one of the most beautiful winelands in the world, those of the Western Cape of South Africa. As far as one can see, the rich vineyards sprawl underneath purple mountain cliffs, amongst some of the most valuable real estate on the continent, all visible from this classic South African township made of corrugated tin, wood scraps, and recycled adverts used as wallpaper. Below these shacks sits the town of Stellenbosch, hosting one of the best universities in Africa.

Like many townships, Kayamandi was founded in the 1950s as a specific non-whites area for laborers who were working on the surrounding farms. It continues to grow to this day, and new houses are clearly visible at the top of the ridgeline. The official census figure of 24000 inhabitants almost certainly is a low estimate. Water, such an abundant necessity in a township, sits tantalizingly close to Kayamandi in the form of irrigation dams for the vineyards.

The contrast in Kayamandi is a gap of extreme wealth disparity, but also a blight hidden in plain sight to the thousands of tourists and holiday makers who travel to the Cape Winelands every year. Stellenbosch is renowned throughout South Africa as the country’s second oldest city, an esteemed university town, and the centre of the wine industry. The stark reality of the thousands of impoverished people living just above the city centre is a woeful reminder of just how unequal South Africa really is.

The footprint of roads from the early 20th century are still visible in District Six.

District Six still exists as a series of empty lots, piles of rubble, and the skeleton of city streets only partially visible amongst the tall grass. Dozens of homeless people construct their shacks in the grass among the rubble, only to be periodically harassed and dispersed by municipal workers and the occasional brush fire. It seems as if every day of the week, at every time of day, a different group utilizes the space, disappearing in a few hours and then leaving the space barren and empty.

Conflicting emotions are present, as the space feels both like a memorial, a cemetery, and a park. Maybe above all else, it stands as a testament to the great wastefulness and futility that apartheid engendered. The refusal to redevelop the land, vacant for decades, speaks to the heightened emotions that still exist around the space.

The former township of Zwelihle, on the edge of Hermanus, provides homes to most of the black African population in the city. Beginning in about 2018, the indigenous milkwood forest at the bottom of the photo, a threatened ecosystem typical along the South African coast, was settled and largely replaced by arriving migrants from other parts of South Africa and abroad. It goes without saying that the holiday homes and wealth condominiums in the lower right part of the photo (called "The Hermanus Beach Club") was built atop the same forest.

Informal settlment alongside the community of Kleinmond.

Zwelihle and Hermanus Beach Club.

The world famous Chapman's Peak drive, winding towards Hout Bay in the distance.