Primrose and Makause, in Johannesburg.

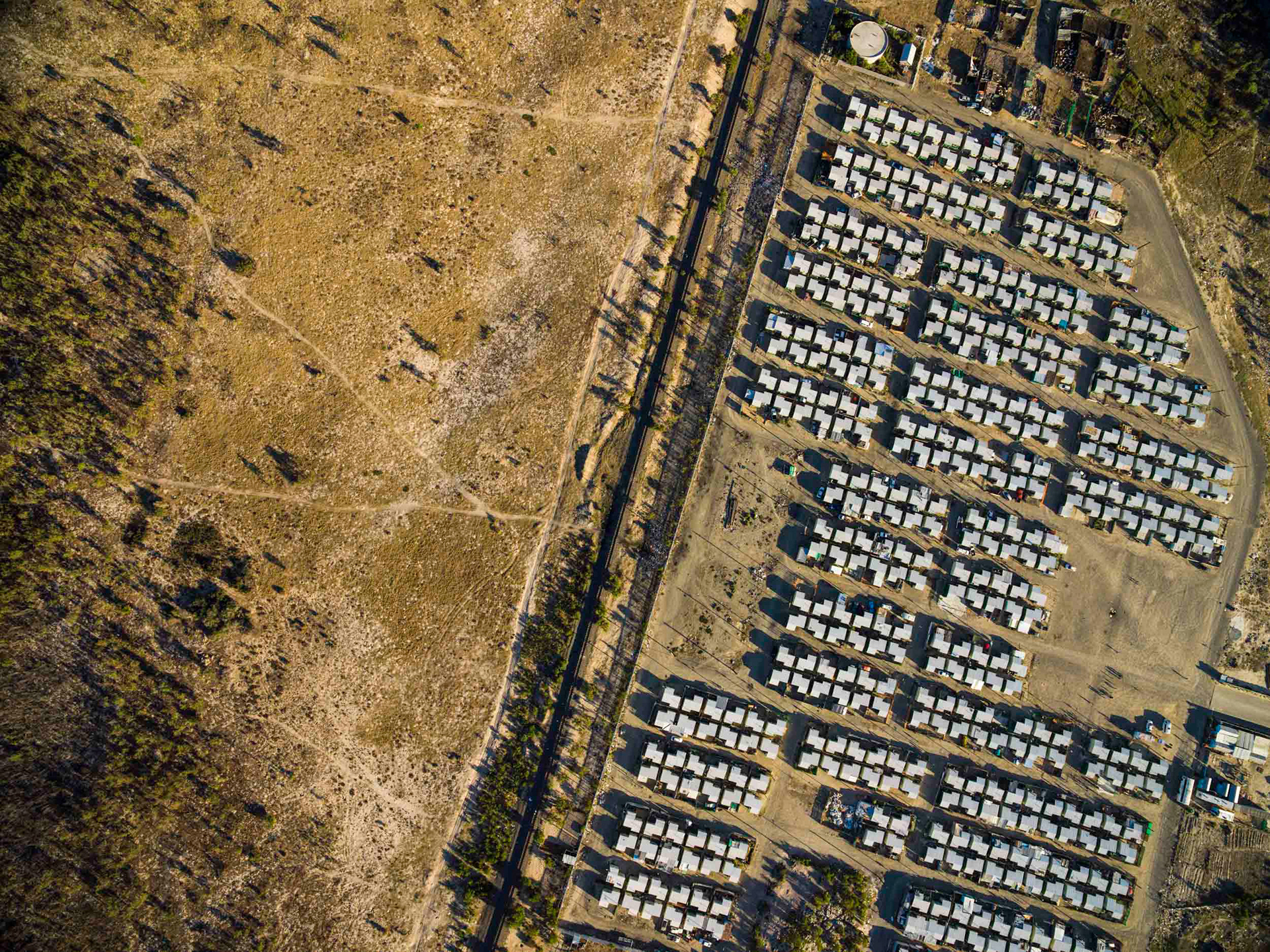

Lake Michelle and Masiphumelele, Cape Town.

Dunoon, Cape Town.

Papwa Sewgolum Golf Course, Durban.

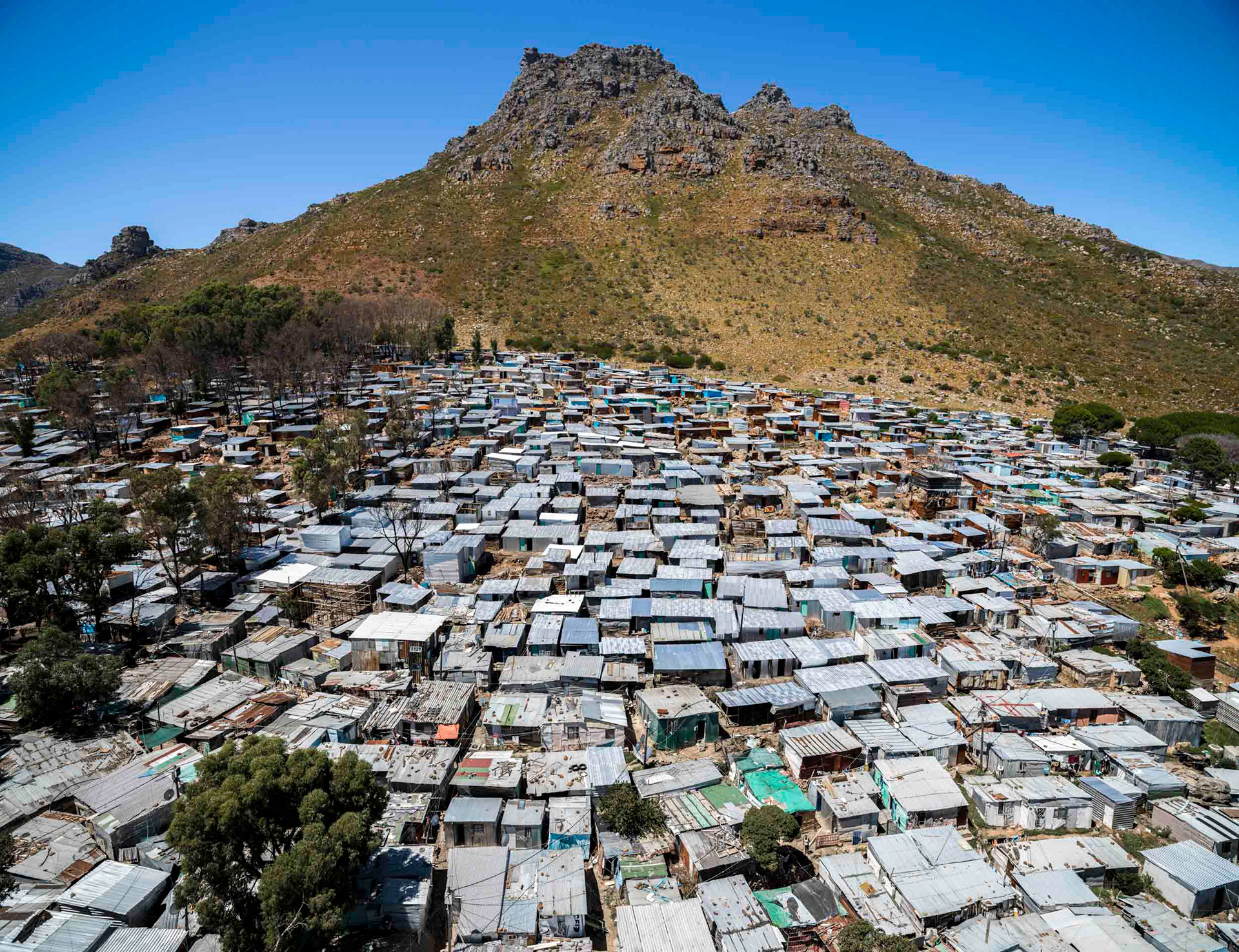

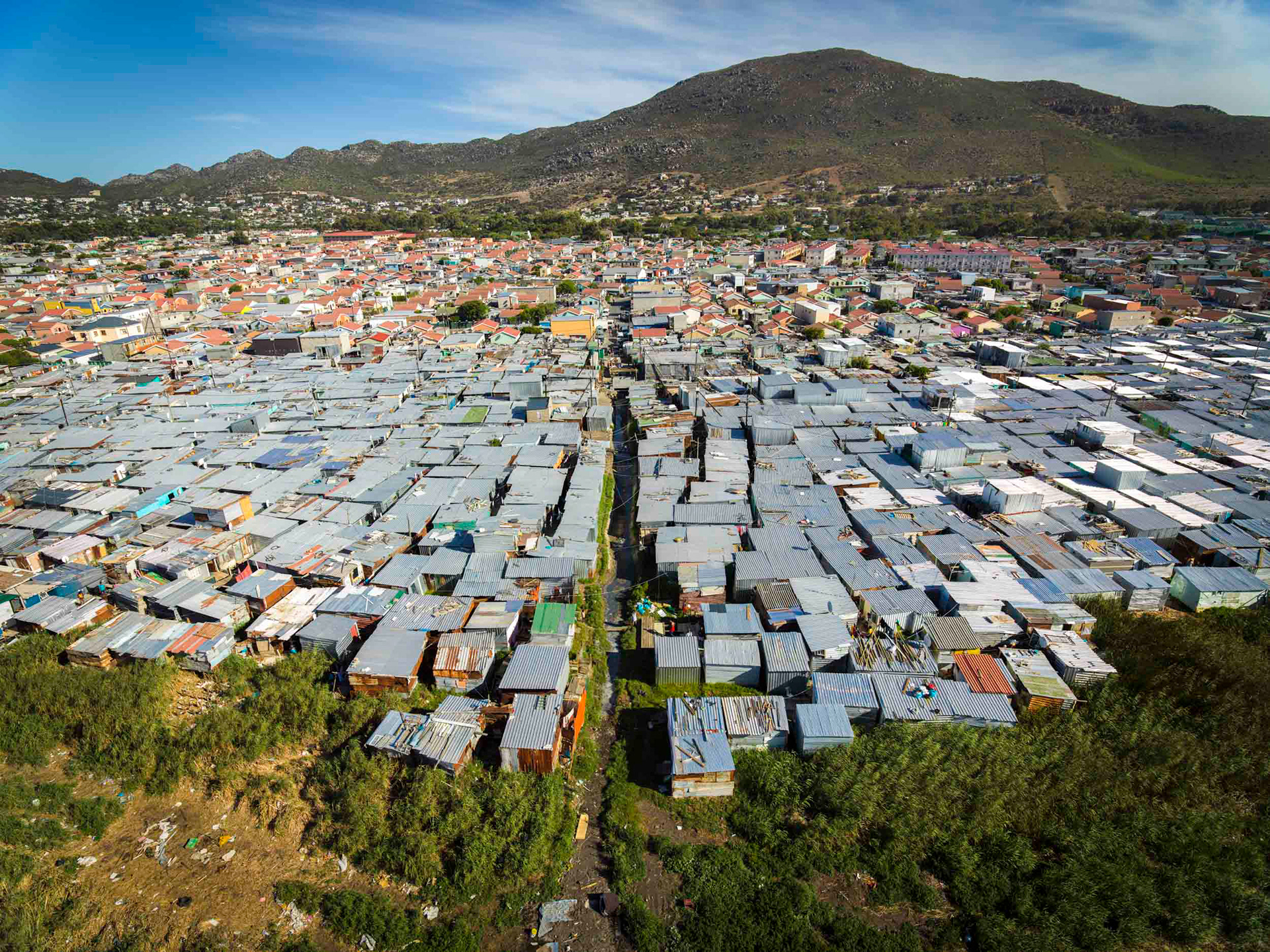

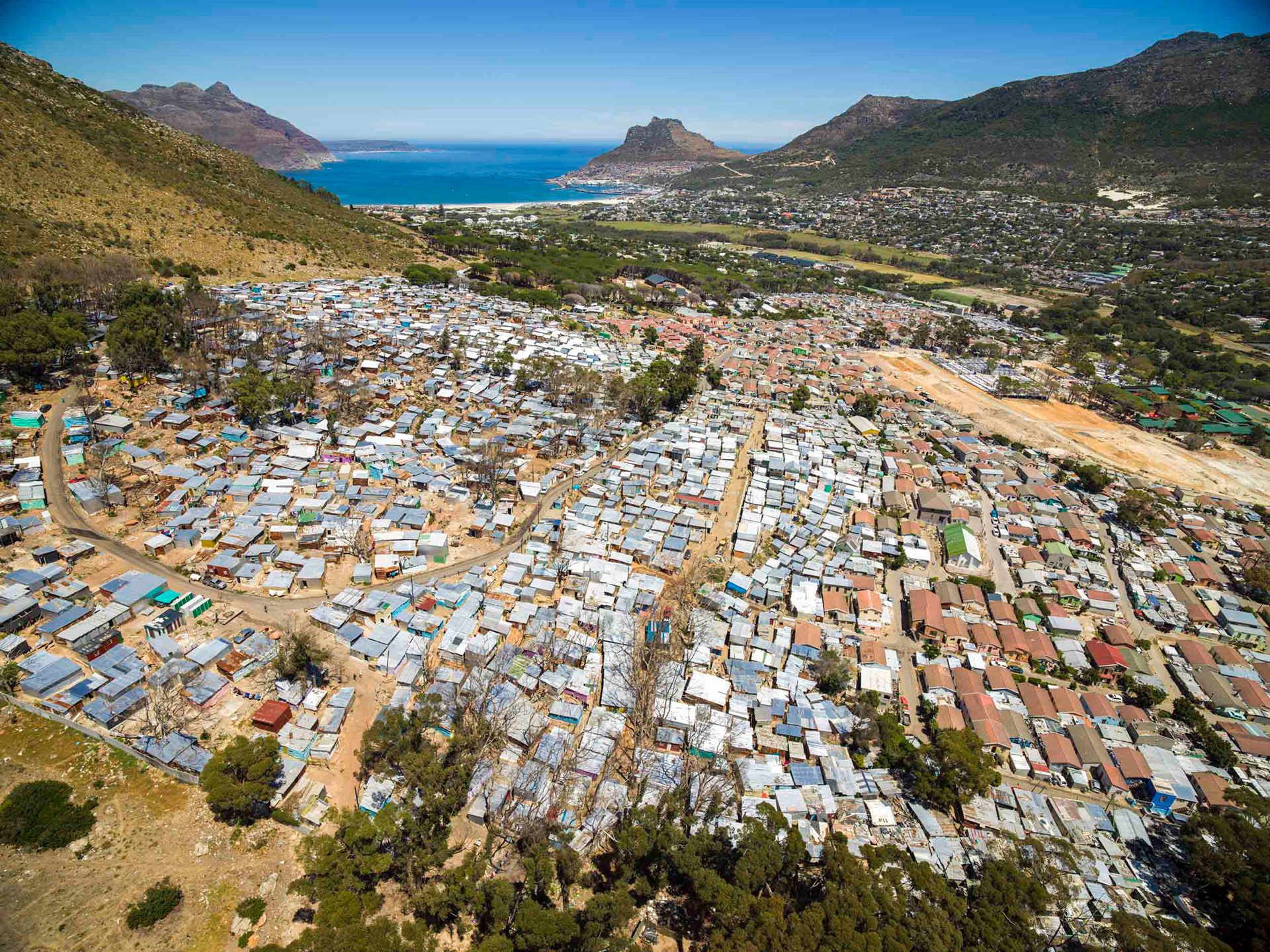

Hout Bay, Cape Town.

Kya Sands and Bloubosrand, Johannesburg.

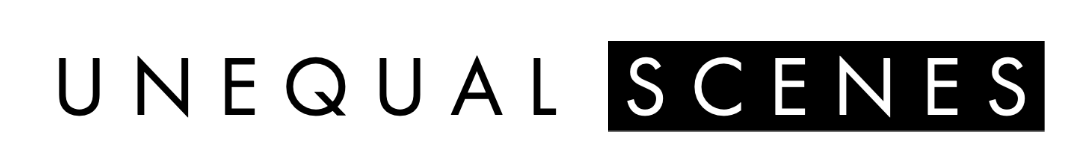

Wolwerivier, Cape Town.

“…I’m a bit more privileged…because I found myself in a situation where I can make a living for myself. I found that because of this piece of land that I’ve got I can give my family a settlement and they don’t have to really struggle to get a house. …But then again you get guys that come out of shacks like this…and this is to me very important…what you make out of yourself. You can also go stay in Constantia (a rich area), wherever you want to go and stay but it determines whether you want to lift yourself up, you want to educate yourself, and you want to make something out of yourself.

I can’t be frustrated, really, honestly, I can’t be frustrated for people staying in nice houses, having nice flashy calls and stuff like that. And I don’t see really, honestly, I don’t see the reason why I should be frustrated.”

Asiphe Ntshongontshi, resident of Masiphumelele, lives in a simple shack made out of tin and wood, along with thousands of other people. When it rains, the area turns to mud, and although the city has dug drainage canals into the bush, rubbish and foul water still occasionally seeps into people's homes. The worst homes are the ones closest to the reeds, as those are the wettest, and the furthest from the road. Nearby, only a few hundred meters away, an electric fence surrounds modern family homes in the gated community of The Lakes.

Danie Kagan lives in a house near the electrified fence which separates her community, called "The Lakes", from the surrounding informal community of Masiphumelele. Danie welcomed me into her home and allowed me a window into her life, living side by side with such great poverty. "I don't think I'll ever get my head around the disparity".

🔹🔹🔹

My image of Primrose and Makause on the cover of Time Magazine, May 2019.