The "most famous photo" of inequality in Brazil: Paraisopolis, São Paulo.

Moinho favela, bounded by the rail lines, at the foot of the largest city in the Western hemisphere.

Santos is Latin America's biggest port by container volume. Only an hour from São Paulo by car, it is surrounded on all sides by favelas, mangroves, and indigenous land.

São Paulo has a unique way to handle the drug problem in its streets: pen all the drug users into a giant open-air user zone, cheekily called "Cracolândia" (Crack Land). This strange attempt at containment has been going on for years. Police monitor the zone for violence but otherwise do not interfere. Far from being outside the city center, this moveable area is usually next to one of the city's main train stations, Luz.

The recreated photo in Paraisopolis, with the famous building, 16 years later.

This empty lot is where a fire broke out, causing a 24-story building to collapse in São Paulo in 2018. Inside were up to 428 people living in a "squat", a type of illegal encampment inside abandoned buildings. Housing is at a shortage in this megacity, forcing residents who don't want to live in the periphery of the city to resort to dangerous and unsafe living conditions such as these. At last count, 49 people were still missing.

An Occupied building in São Paulo, just off the famous Avenida Paulista. The graffiti on the outside of the building is a typical style of “pixação”, which is a unique form of highly stylized protest/symbolic writing found all over the city. Pixação is especially prevalent and popular in São Paulo and used for diverse reasons: as a type

of calling card, communication, or even protest art. Pixadores use their skill, climbing prowess, and daring to reach the highest and most dangerous locations in a city famous for its horizon full

of tall buildings.

The Occupy 9 do Julho (9th of July), perhaps one of the most famous Occupy movements in the city of São Paulo, is located in one of the most expensive neighborhoods near the city center, and hosts around 124 families since 2016. Housing is at a premium in highly centralized São Paulo, and many people need to travel on overburdened public transit hours each way from the peripheral parts of the city to work.

The majority of residents are not asking for free places or shelters, but rather the right to the city: fair conditions to finance a house, a fair monthly pay and rent that a worker can afford, and to have more equal access to valuable places of the city. With a small textile cooperative, a community garden and open weekly organic lunches every Sunday, MSTC (Movimento Sem-Teto do Centro, or Homeless Movement of the City Center) works to create dialogues with different movements, collectives, academic groups and society in general. Carmen Silva, the main leader, is now running for the São Paulo

state parliament.

Gilmar and Adysson, friends living in the Occupy Mauá in central São Paulo, look down at the festivities for the 15th anniversary of the Occupy’s founding. The building, which used to be a hotel, fell into disrepair and was abandoned after the original owner died, leaving the family with an unrecoverable debt in unpaid city taxes. Today, it is one of the most successful occupies in the city, with over 200 families (and over 1,000 people) living in an intentional, organized community inside its walls.

Occupies are part of a series of vital social movements which work to provide safe, dignified housing in a city that lacks 360,000 houses and where many people take hours to commute from the peripheral areas. In Mauá, the spirit of resistance and political lineage is strong, with a large mural depicting Maria Carolina de Jesus in the entrance (a famous resident of the periphery, a black woman who wrote eloquently about her experience in the favela in mid-20th century São Paulo) and memorials to the occupation itself and to Marielle Franco. All the leaders here are Black, and the majority are women. There is a strong connection with the arts, and in particular, graffiti, and the interior of the space is covered in memorials, political slogans, and other artwork.

Gilmar, 11, at his home in the Ocupacão Mauá, a peaceful occupied building in the city center of São Paulo, housing 237 families. In the background is the train station Luz's clock tower, which for decades dominated the skyline of São Paulo.

Daví is one of the leaders and a Xondaro (warrior) of the Jaraguá Guaraní community in São Paulo. The Guaraní are the original inhabitants of this part of Brazil that is today the most populous and powerful: a region stretching from Paraguay, through northern Argentina, and all the way up the southeastern coast, including the cities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Their traditional forest lands (the Mata Atlantica) are the most devastated in Brazil, and unlike Indigenous groups in the Amazon, they also have “urban issues”: Gentrification, crime, property speculation, and the allure of city life.

On the day I visited, Daví was just coming out of a year-long mental anguish, during which he saw visions, tried to harm himself, and suffered terrifying voices. In no uncertain terms, the community sees the destruction of the forest, mental health and the survival of the people intimately intertwined. To this end, the Guaraní are using their proximity to the city to take advantage as much as possible of education opportunities, and alignment with national movements.

The traditional lands of the Guaraní people, inside the city limits of São Paulo, are technically protected land in the form of both the Jaraguá Aldeia and Jaraguá State Park. But the insatiable appetite of a city with 22 million people to grow and expand its low-cost housing means that there is constant pressure from both developers, and semi-legal low-income housing projects. The relationship between the environmentally protected areas (the park) and the Guaraní community is complicated by the fact that a large part of this historical and sacred land is off-limits to them. The community itself is proscribed to 8 square hectares, with little space to farm and engage with the forest in a traditional way.

New aldeias established since the park’s inception are at risk of being seized dependent on the outcomes of the Marco Temporal case working its way through the legal system (and a major driver of the ATL event and the APIB movement). This is not limited to Jaraguá - the Guaraní inhabit the most densely populated section of the country, a forest which has been decimated by deforestation and urbanisation. When asked if they saw the encroachment by favelas onto parkland as a fundamentally antagonistic relationship, the Guaraní that I talked to responded no. They see both communities as participants striving against the state in the quest for decency and good living.

Palafitas, or stilted homes, are a unique feature of Santos' architecture, housing poor families who otherwise cannot find land to build on. This one suffered a large fire in July 2025, burning down almost 100 structures in a matter of hours.

This painting, and two others like it, is a trompe d'oleil, forming a word only when looked at from the correct angle. It was created by the Spanish street-art collective Boa Mistura, as part of their Luz nas Vielas project in the Vila Brasilândia favela in São Paulo. The murals include the words “Poesía” and “Mágica” — meant to uplift the neighborhood by highlighting local beauty, improvisation, and community life. The installation used purple and green tones and is scattered across alleys and staircases, transforming mundane bricks into a living, poetic mural of memory and hope. It is less about graffiti and more about a collaborative art project.

In this city of 20 million, with endless rows of yellow and white buildings, it is public art which helps Paulistas cope with an otherwise overwhelming feeling of being trapped in the urban jungle. It is a city alive with murals, pixação and graffiti.

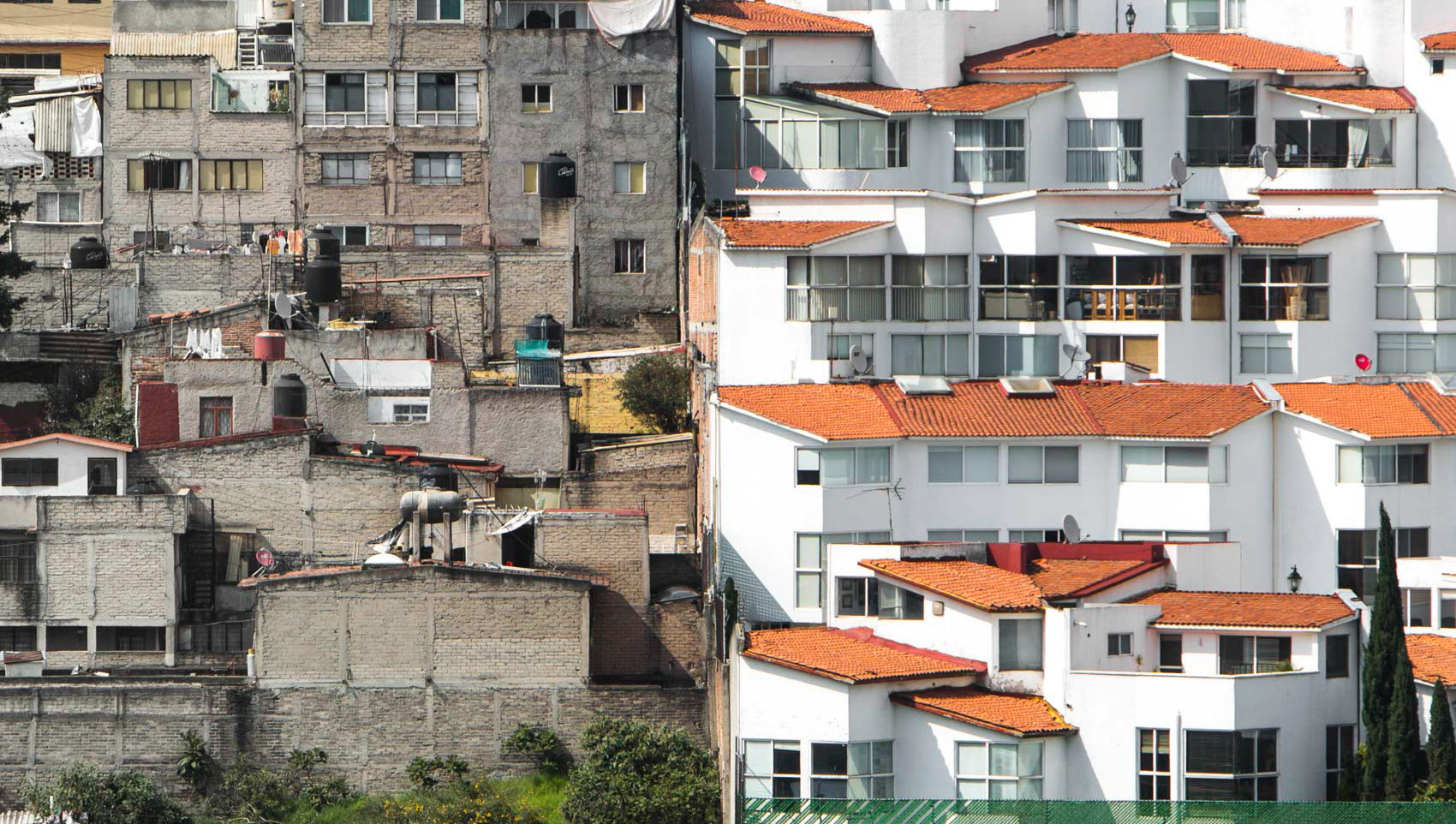

Vila Andrade & Paraisopolis, São Paulo.

Tatuapé, São Paulo.

Apartment buildings frame a favela in the city's western suburbs.

Historically, the wealth generated by coffee exports and port activity never reached the average worker in Santos. Instead, port workers, stevedores, and domestic laborers built informal homes wherever they could. Favelas now dot the hills in Santos, as well as large stilted communities called palafitas.

São Paulo’s skyline is anchored by the Edifício Copan, Oscar Niemeyer’s signature wave‑curved residential tower, rising 32 floors with over 1,160 units—all housed behind its sinuous concrete façade. Completed in 1966, it remains the largest reinforced‑concrete structure in Brazil and was envisioned as an architectural symbol of a diverse, urban society. Designed to blend millions of residents across social classes, Copan was built during the city’s mid‑century boom and still contains shops, restaurants, and apartments side by side. Its undulating form challenges São Paulo’s rigid grid—literally and metaphorically curving public space into a vast dialogue between formal modernism and populist living.

The rich suburb of Morumbi sits on a ridgeline with a direct view of Paraisopolis.

Guarujá, just across the bay from Santos, is a patchwork of luxury condos, crumbling fishing villages, and dense Atlantic rainforest. Once a quiet retreat, the area boomed during Brazil’s postwar expansion, becoming a playground for São Paulo’s elite. But behind the beachfront high-rises, inequality runs deep—many service workers live in precarious housing tucked into the hills, separated from other communities by undeveloped forest.

The Rodoanel Mário Covas, São Paulo’s massive ring highway, passes near the northern edge of Brasilândia, a dense peripheral neighborhood historically underserved by infrastructure.

Designed to divert cargo traffic around the city, the Rodoanel cuts through forested hills and skirts low-income communities like Brasilândia, physically separating them from wealthier zones and reinforcing patterns of spatial inequality. While the highway was billed as progress, for many residents it brought disruption: displacement, noise, and further marginalization without real access or benefits.

The iconic towers made famous by Tuca Vieira's 2004 photo of inequality in the Paraisopolis favela. Now the towers are beginning to fall into disrepair - since the favela has grown, few people want to spend money on a flat overlooking a slum, no matter how nice the pool is.

Fishermen walk hundreds of meters out onto this rail bridge to catch fish from the productive waters of the estuary of Santos. This body of water, formed by a series of rivers emptying the hilly interior, is vital to mangroves, biodiverse fish, bird, and animal populations, as well as the people who have lived here as fishermen for centuries (or longer). As the port expands, dredging needs to take place, disrupting this vital ecosystem and inviting all the hazards that a large port brings to a sensitive area like this.

"Piloto", one of the residents of the palafitas (stilted houses) of Santos, discusses his battle with Covid that almost killed him. His children, who live with their mother, are what keeps him going. His tattoo reads, "Caio - My Son, My Maximus"

The mangroves of Santos are a highly productive ecosystem. The residents of Ilha Diana (in the background), population 100, mostly live by arranging fishing tours. The expansion of the port threatens them, and the fishing grounds, by disrupting the balance between fresh water and salt water with dredging, pollution and increased marine traffic.

Santos, Brazil’s historic port city, was once the global epicenter of the coffee trade. In the 19th century, millions of sacks flowed through its docks, fueling both Brazil’s economy and the fortunes of coffee barons. But that prosperity was built on the backs of enslaved Africans and poor migrant labor. The port remains Latin America’s busiest, now moving containers instead of beans—but inequality still defines the city. Opulent mansions and office blocks stand in front of working-class neighborhoods and aging port infrastructure. Santos is a reminder: global trade routes often begin in places shaped by exploitation and uneven progress.

Jaguaré, São Paulo.

Avenida 9 do Julho, São Paulo.

Once the tallest building in Latin America, the Altino Arantes Building—now called Farol Santander—stands as a symbol of São Paulo’s financial ambition. Built in 1947 for the state bank Banespa and modeled loosely on the Empire State Building, it rises 161 meters into the skyline. Today, the tower has been repurposed into a cultural center, featuring art exhibitions, cafés, and a panoramic observation deck. Its transformation from banking monolith to public space reflects São Paulo’s shifting identity: from industrial capital to cultural metropolis, from rigid formality to layered reinvention.