Bosque Real Country Club and Lomas del Cadete, in the foothills of Mexico City.

A large housing development near Mérida extends into the Yucatán jungle. The controversial "Maya Train" is visible in the background, which will connect communities in the region in a giant, expensive rail network, even at the expense of the natural environment. The project is a personal focus of Mexico's former president (known as AMLO) and a perennial thorn in the side of Indigenous and environmental activists.

Gated communities in the foothills of León, Mexico are fenced off and slated for development. Affordable housing that is eco-friendly, parks and other civic improvements compete against private developments here and in many other parts of Mexico, where money talks.

Álvaro Obregón (right) and Santa Fe (left), sites of immense disparity in health outcomes from Covid-19 during 2020-2021.

Santa Fe, looking towards Álvaro Obregón and the city center on a smoggy morning.

Santa Fe, an upscale "new downtown" in the foothills of the mountains above the smog-choked center of Mexico City.

An informal community built on a defunct train track forms a linear stripe across the landscape in Naucalpan, Mexico City.

Gated communities in the foothills of León, Mexico.

The informal community stretching along the defunct railroad track in Naucalpan, Mexico City, extends for kilometers.

The El Conde pyramid, a Mesoamerican heritage site, sits across the river from a collection of train cars which house dozens of families in Naucalpan, in the Mexico City metro region. The city government has plans to move this community and create a new transit hub for the region.

Downtown Mexico City at dawn.

Mexico City at the time had a huge housing shortage, and in 1971 President Luís Echeverría Álvarez stated that he would begin to regularize informal land holdings in the city. This precipitated a rush of people to "invade" the land of Pedregal de Santo Domingo, one of the largest such land invasions in Latin American history.

Coyoacán, CDMX, with a tianguis and multiple fenced communities intersecting on one focal point.

Pedregal de Santo Domingo circa 1971. Photo courtesy of Sarah Farr.

Pedregal de Santo Domingo circa 1971. Photo courtesy of Sarah Farr.

Google street view maybe the clearest way to see the disconnection between Pedregal de Santo Domingo (bottom) and the wealthy enclave of Romero de Terreros (above). Courtesy Google Maps.

Coyoacán and Pedregal de Santo Domingo, separated by an obvious concrete wall.

The same view, looking west.

A private golf club with residences, surrounded by the sprawling metropolis of CDMX.

I've always been interested in the way that golf courses look in relation to their surroundings on a landscape, and in a city like Mexico, they stand out like refreshing private oases among the endless concrete slab. This course sits high in the mountains which ring the city, at an altitude of over 2500 meters, a place where the elite have carved out a new downtown, new highways, new private estates, malls, and of course country golf clubs - Santa Fe. This glittering wealth often bumps up against uncomfortable realities, as the peripheral neighborhoods contain some of the poorest and most vulnerable people. COVID-19 has hit these neighborhoods, for example, disproportionately hard.

Like the author of the book "Privilege at Play: Class, Race, Gender, and Golf in Mexico" (Hugo Ceron-Anaya), I don't hold any enmity towards golfers, and I don't necessarily hold prima facie enmity against the wealthy either. (I do, however, have a chip on my shoulder for book designers who use an image of Sao Paulo on the cover of a book about Mexico City)

Golf courses generally come with gates, security, and a marked difference in environmental appearance.

A golf course in the foothills of the mountains, at 2500m altitude.

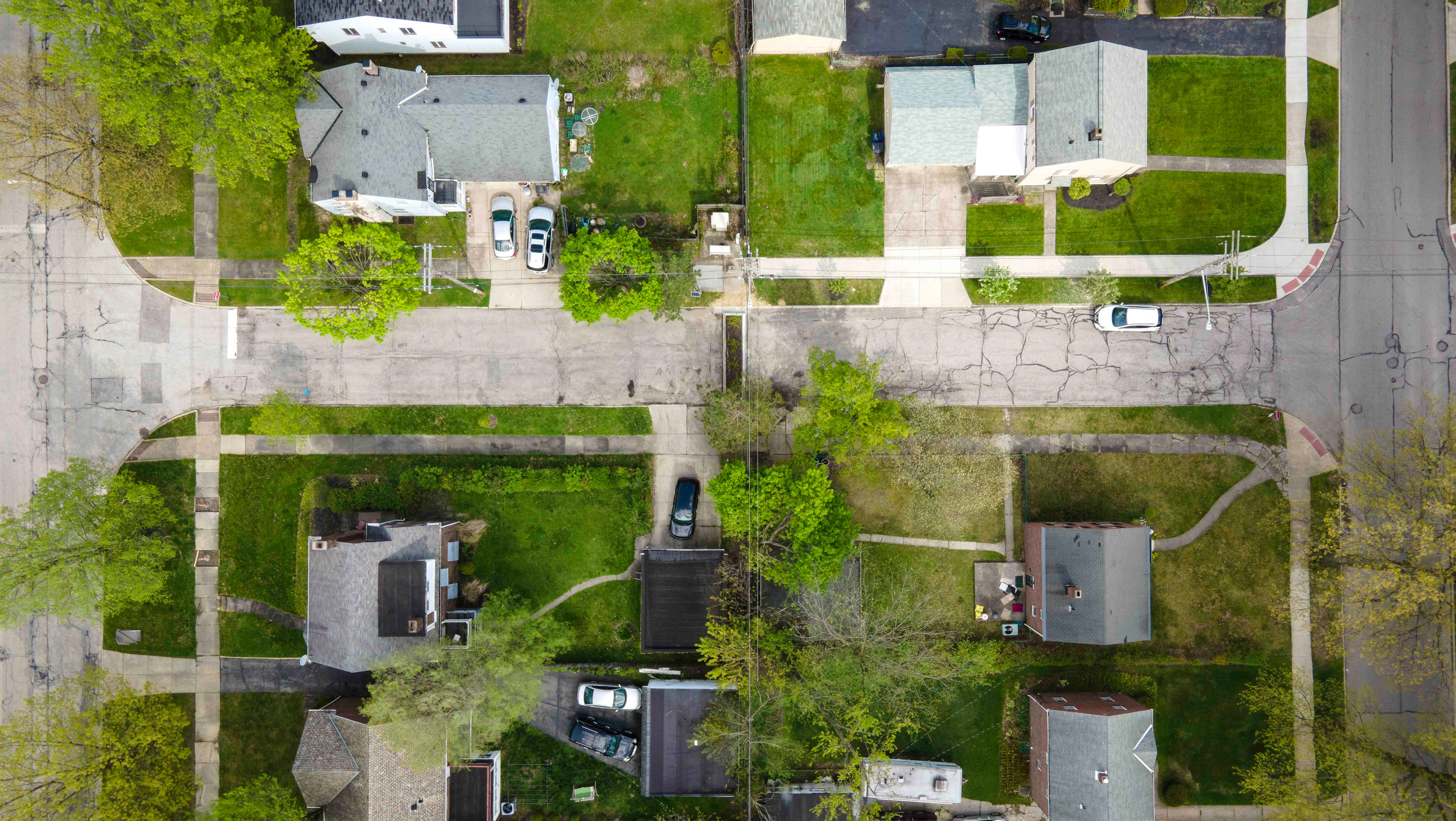

Innovative traffic solutions for the hilly environment have highways running underneath entire communities, rich and poor.

A strangely beautiful and symmetric separation between rich and poor in Santa Fe.

Santa Fe.

Santa Fe.

Lomas Haciendas, in the northern suburbs of Mexico City.