The so-called Wall of Shame in Lima, Peru, began rising in the 1980s when wealthy residents of Las Casuarinas built barriers to separate their properties from the growing settlements of Pamplona Alta. Stretching several kilometers across the hills, the wall expanded through the 1990s and 2000s as inequality deepened. It still stands today, a visible line between privilege and exclusion in the capital’s south.

Walls in Lima extend for kilometers, even over sparsely populated mountaintops, in a bid to keep rich and poor separated. This one connects roughly with the same walls in the pictures above and below.

The Wall of Shame has existed for decades in Lima, a kilometers-long barrier of concrete and barbed wire. It exists as a proxy for the failure of an effective state response to informality, inequality, and crime, built along class lines, rather than ethnic or religious lines.

The simple fact is that the wall works - San Juan de Miraflores, in the district of Pamplona Alta, is the second least safe neighborhood in Lima, according to the NGO Ciudad Nuestra. On the other hand, Surco, in the district of Las Casuarinas, is the fourth safest neighborhood in Lima.

Wealthy suburbs carved into dusty hillsides dot the area of La Molina, in Lima's east.

The "Wall of Shame" in Lima from a different angle, showing the vast difference in access to green space in this arid city, largely treeless city.

Lima is dotted with sparsely populated holiday housing developments like in Punta Negra, where land speculation seems to be a popular sport.

Walls enclose green lawns and swimming pools in Lima, sometimes extending over hilltops in Las Casuarinas.

Walls are omnipresent in Lima, like these ones, along the side of the road, in the empty desert on the way to Pucusana.

Lima's suburbs are growing at such a rapid pace that they threaten archealogical sites like this one near Julio Cesar Tello. The pressures of migration, housing, and jobs can seem much bigger than the need to preserve history, even at the expense of losing it forever.

Informal housing on every hilltop - migrants from the interior of the country looking for better prospects move to Lima, many of them ending up in dusty hilltops like this in Villa Maria del Trionfo.

Enedina Soto lives in one of the informal houses in Villa Maria del Trionfo with her husband, peeling garlic for a living. She normally walks down the steep slope to sell it in the market, but had to stop because of pain in her wrist that she refuses to get treated because of mistrust of doctors.

Villa Maria del Trionfo in Lima and a hulking cement plant in the distance, encircled by the omnipresent walls.

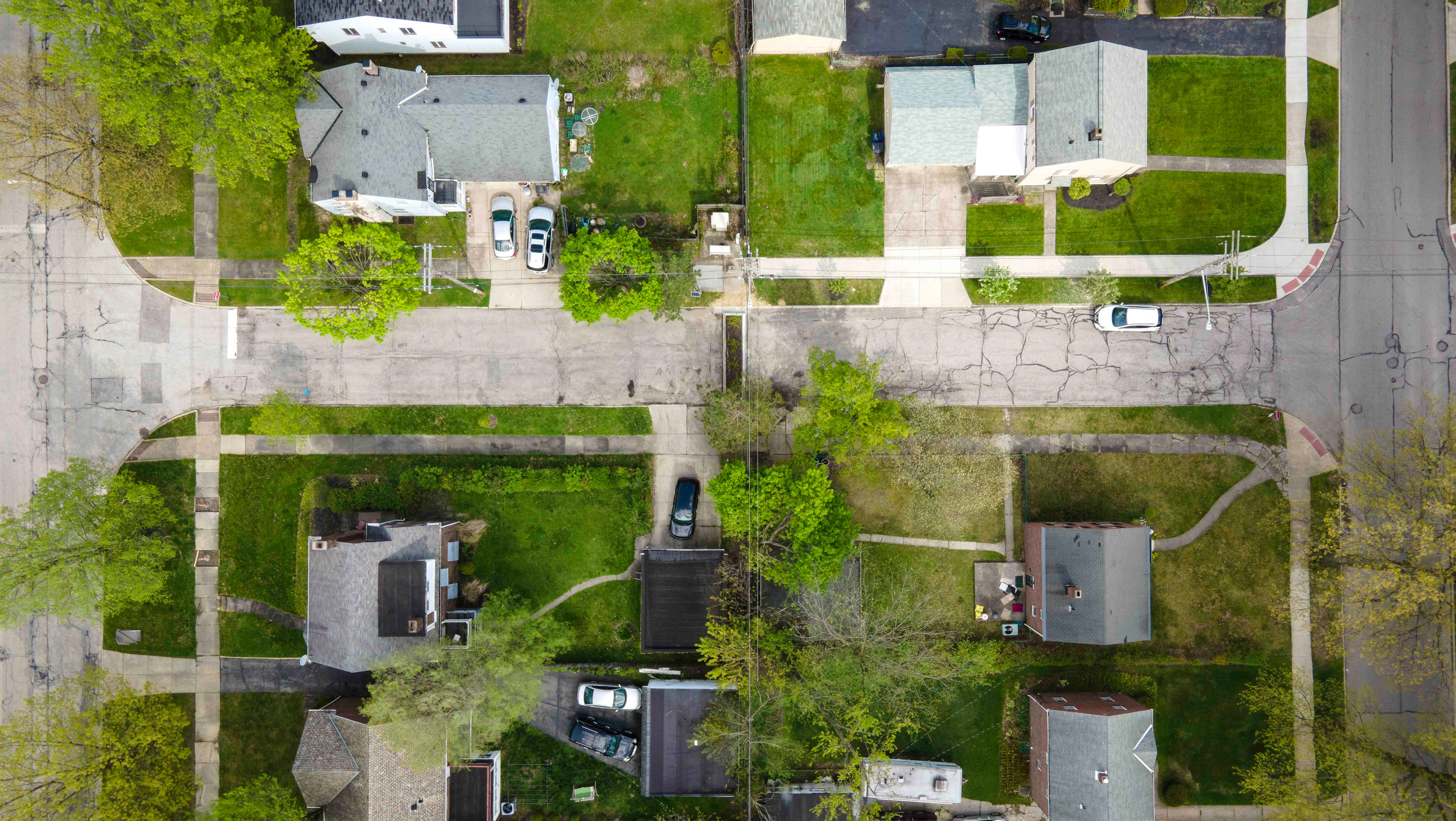

Rich and poor meeting in Lima's eastern suburbs.

Beachside mansions and resorts in Pucusana, about 45 minutes south of Lima, below the informal communities on the hillsides above.

Country Club El Bosque Sede Playa opposite the dusty communities of Punta Negra, south of Lima.

An oil spill coats the beach in Ventanilla, Peru on January 19, 2022. Reports say the underwater volcanic explosion and subsequent tsunami originating in Tonga were to blame in dislodging an oil tanker near Lima at a refinery owned by Spanish company Repsol. As of writing, the Peruvian government has banned four executives from leaving the country, and sentiments from the population are running high.

Illegal gold mines stretch for tens of kilometers near La Pampa, in the Peruvian Amazon. All of it is illegal. Miners use mercury and other toxic chemicals to bind to gold which has been sluiced out of pits dug near rivers.

In addition to mercury poisoning, deforestation, mosquito breeding, and crime, there is the specter of political mismanagement and a confusing security environment which seems to vex even the most jaded Peruvian. In 2019 the military effectively shut down these gold mines, declaring them illegal and smashing the pumps and sluices that are the lifeblood of the operations. However, only two years later, the towns of La Pampa, Nueva Arequipa, and others are thriving. One only has to drive on the Interoceanic Highway to Puerto Maldonado to experience these boom towns in their full glory - delivery drivers on motorcycles and tuk-tuks snaking through heavy truck traffic, sex workers huddled under rickety wooden awnings beckoning customers, children running pell-mell, multi-story buildings half constructed over bright orange, polluted mudflats. It's a modern day gold rush, in full view of the world, in full view of anyone who cares to intervene, and quite possibly one of the strangest communities you can easily drive to in the world.

Nueva Arequipa, the boom town at the center of the devastated Madre De Dios gold mining region. Peru isn't just a bit player in the gold mining industry - Peru is the world's sixth-biggest exporter of gold, and the largest in Latin America.

Devastating damage from open-pit gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon.

Toxic runoff from illegal gold mines into one of the tributaries of the Inambari near the town of Mazuko.

Chincerho is the site of the new international airport being built to replace the outdated, dangerous one in the center of Cusco. It will revolutionize the tourism industry in the Macchu Picchu region, but it has also been beset by controversy.