Rich and poor in Chapinero, one of Bogotá's nicest suburbs.

The Suba Hills, dividing rich and poor in Bogotá's north zone.

Chapinero, where rich and poor back up against the mountains.

Different strata households exist side by side in the foothills of the Andes, where informal housing took off after decades of migration from rural areas.

Poor neighborhoods classified as "2 or 3" on the social strata map sit high above the Chapinero neighborhood, one of the city's nicest.

New building construction in the El Consuelo section in the south of the city.

Downtown Bogotá.

A map of the social strata locations in Bogotá.

In Chapinero, informal housing is sandwiched between expensive new development in one of Bogotá's nicest districts, and the steep mountains just behind.

The high-altitude capital has a system of cable cars, which lead to the highest neighborhoods in the poor south zone of the capital.

The cable car to the top of Ciudad Bolivar is a popular innovation in public transport, made famous in Colombia, that has spread all over Latin America.

Bold and interesting designs in the social housing projects in the south of Bogotá.

This house (top of the image) is currently being sold for almost 19 billion pesos. Below it stretches a strange mix of informal, poor, rich, and farms on the west slopes of the Suba Hills, where strata "6" and strata "1" meet.

One of the many innovations that successive mayors have done in Bogotá to improve the lives (or the perceptions) of the residents in poor communities is to paint their houses. Here, the communities of Santa Cecilia and Cerro Norte are painted to look like the wings of a butterfly when seen from just the right angle.

The neat line of a fence separates poor and rich in the Suba Hills.

The Suba hills are a fascinating patchwork of farms, informal housing, mega-mansions, and gated estates.

The sunset is never guaranteed in Bogotá, but when it comes it illuminates the Andes mountains perfectly. Here, the Strata 1 community of Villa del Cerro is juxtaposed with the gleaming new Faculty of Sciences building at Javeriana University, in the affluent Strata 5 suburb of Chapinero.

The building is being built with a high degree of eco-friendly features, including these fascinating golden baffles on the facade. I find it a very beautiful building.

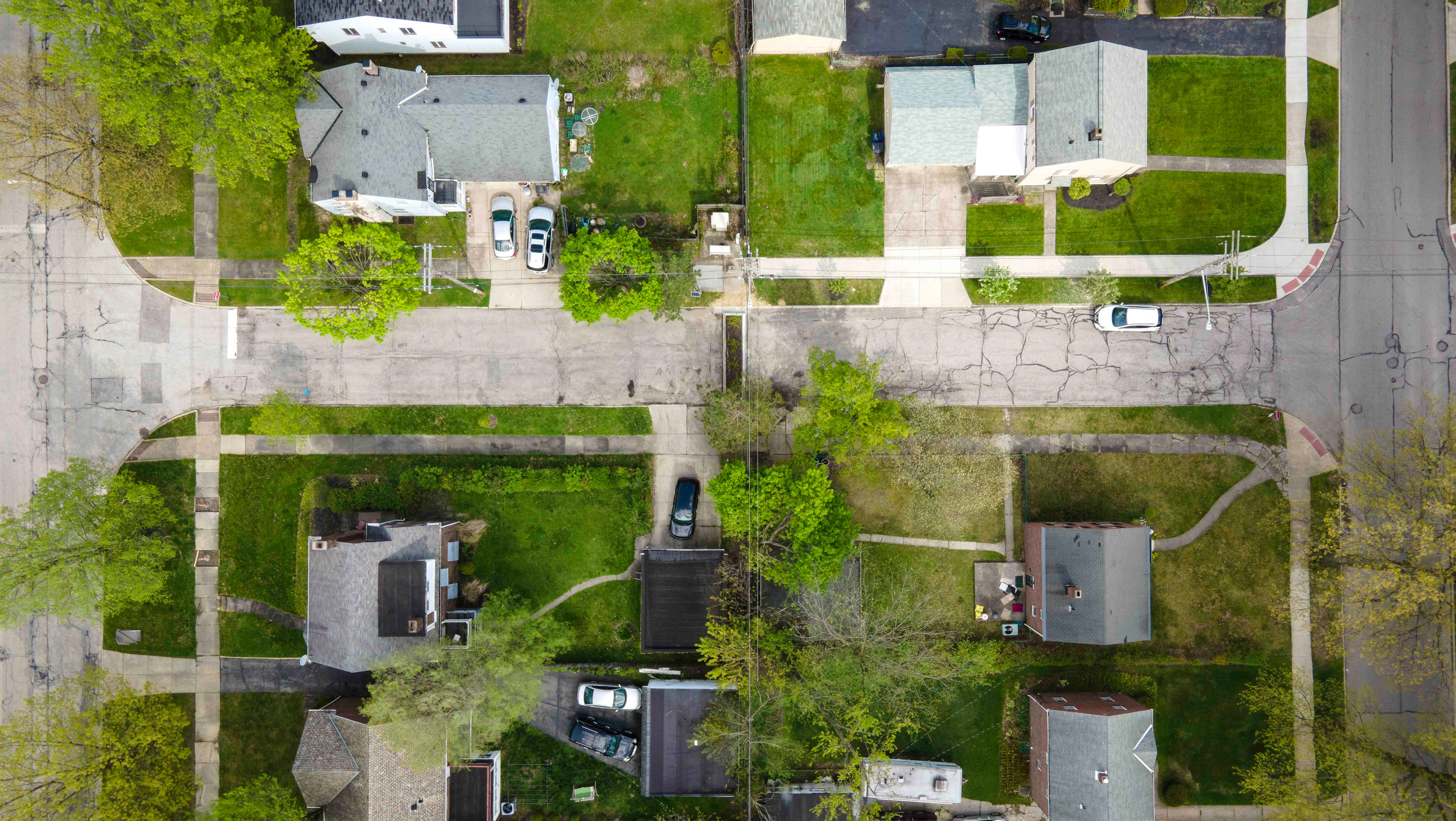

Little informal communities that are hidden from view become apparent when seen from directly above, like this one in Chapinero.

Extreme inequality between neighborhoods representing Strata 6 and 1 in Bogotá's richer suburbs.

Downtown Bogotá in the setting sun, with the barrio of Villa del Cerro and the rich neighborhood of Chapinero in the foreground.

Calasanz Seminary, next to the neighborhood of Villa Del Cerro.

Chapinero.